That’s The Last Straw! – Why your reactive dog sometimes over reacts “out of nowhere”

Story time!

Recently, I had a moment with a client’s dog that got me thinking a lot about trigger stacking, or what we’d more casually call “the last straw.”

River is a very sweet but nervous and frustrated medium-sized dark brown dog with slick short fur and white socks. She doesn’t know what to do with herself when she can’t greet new dogs immediately, and she is uncomfortable with strangers, and with people who ignore her when she asks for space. She’s familiar with me, and typically will take treats from me or hang out nearby, but doesn’t want me to pet her, no matter how cuddly she is with her family.

River is a very sweet but nervous medium-sized dark brown dog with slick short fur and white socks. She doesn’t know what to do with herself when she can’t greet new dogs immediately, and she is uncomfortable with strangers, and with people who ignore her when she asks for space. She’s familiar with me, and typically will take treats from me or hang out nearby, but doesn’t want me to pet her, no matter how cuddly she is with her family.

This day, she had been home alone for a lot of the day while her owner was at work. When her owner came home, she picked up River to bring to a semi-private lesson, where she would be around unfamiliar dogs and people, as well as around me and my dog, who she is familiar with.

She was frustrated during the beginning of the lesson, but became more able to handle it as time went on. A couple times throughout the lesson, the dogs got a little overwhelmed, and we gave them more space whenever they needed it. Eventually all dogs were hanging out relaxing at a distance from each other, practicing being calm in each others’ presence without greeting each other or over-reacting.

At the end of the lesson, the person and dog River was unfamiliar with had left, and I’d put Juniper away and went over to talk to her human. I offered River a treat from my hand as we talked (which was already pushing it), instead of from the ground. River sniffed it, looked at me, and then looked away and leaned her body away from me.

At that moment, I made a mistake. What would have been wise was listening to River’s soft no, and backing off. I could have put the treat on the ground for her to choose if she wanted it or not. She had had a lot happen that day, and she was worn out and reaching her limit.

What I did instead, was pause, then offer her the treat from my hand one more time, a little differently.

What happened then was that River reacted – not being heard in that moment was “the last straw” for her. She growled, barked, and darted away from me toward her human.

It would be easy to look only at that snapshot in time and think “Wow, she over-reacted! All I did was offer her a treat!” But in reality, that’s not the whole picture. This is what trigger stacking is all about: There were a bunch of stressors throughout the day that led to River’s reaction. Each one added on to the previous one, so that being unheard and pushed further when she said “hey, I’m uncomfortable taking this from you” was Too Much.

In that moment, River’s reaction was completely appropriate – she didn’t escalate any further than it took to be heard, and communicated as best as she was able to. It was also a reaction she would not have had to being offered a treat to me any other day. She was trigger stacked.

Her reaction wasn’t about being given a treat. Her reaction was about being overwhelmed, and not being listened to when she said no.

So, what is Trigger Stacking?

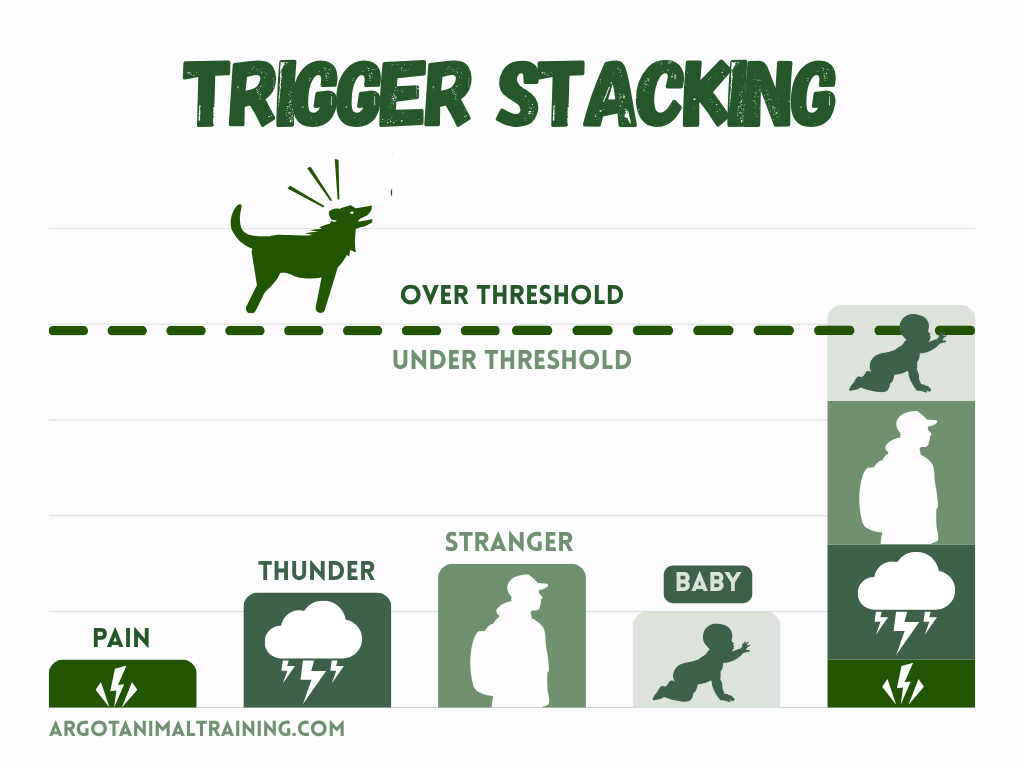

Trigger stacking is when there are multiple stressors in a short period of time, and it can lead to your dog having what seems like a big reaction to something relatively minor… because they aren’t just reacting to the stress of the most recent thing, but to the collective stress of Every Stressful Thing that happened recently.

This doesn’t just happen to your dog, it can happen to you too! Have you ever had a day where every little thing seems to go wrong, even though nothing big does? After a certain number of things “going wrong”, you feel like the next thing is going to be The Last Straw!

Think of it like this: we all have a “threshold” at which everything becomes “too much.” It’s when you hit your limit. Each stressor we experience puts us a certain amount closer to that threshold (and time or some relaxing activities can take us further away from our threshold). If a lot of things happen in a row, they “stack,” which puts us “over threshold” - where we stop being in our Thinking brain and start being in our Reacting brain.

How can this help your reactive dog?

Knowing how this works can change the game when you’re working with your own reactive dog.

Every day, our dogs experience things that move them closer to their threshold (stressors), and things that move them farther from it (things that are relaxing), and so do we! Knowing how this works and what stresses and relaxes your own dog can give you the power to reduce your dog’s reactions through their environment.

This can help you set your dog up for success as you work through your training program, and to know when it’s just not a good day for training.

Know when to call it a day

Sometimes, if you know that your dog is already a little on edge and close to their limit, the best thing you can do for you and your dog is to call it a day. Especially in the beginning states of training or during stressful days or weeks, it’s important to take Decompression Days.

Whenever our dogs experience a stressful event, their nervous system reacts, and it can take time for our dogs to recover to their baseline afterwards. If you’ve ever felt like you have a “stress hangover” the day after a really hard day, you’re familiar with the feeling of needing recovery time.

Watching your dog’s body language and how readily they hit their limit can help you tell if maybe taking some time for them to decompress might help.

In general, your goal with decompression days is to limit their exposure to stressors through management, and introduce calming activities.

Reduce background stress

Background stress can put your dog closer to threshold before anything unusual has even happened in the day. Finding ways you can reduce stress, whether all the time or just for today, can give your dog a bigger window of tolerance before they lose their cool.

Some things you can consider when thinking about background stress are:

Pain

Does your dog have any daily pain, achiness, or discomfort? If there’s a chance they might, a vet check to get pain better managed can have a big impact on behavior.

Sounds or sights when home alone

If you have a reactive dog, odds are high that they might find the sight or sound of neighbor people, dogs, cars, or wild animals upsetting or over-stimulating, depending on their triggers. Strategic use of window films, white/brown noise machines, and more can help ensure they’re not being over-exposed to these stressors when you aren’t there to guide and support them in training sessions.

Be your dog’s advocate

If other people, pets, or children are frequently invading your dog’s space or ignoring their signs of discomfort, it can increase their baseline stress levels substantially. Be your dog’s advocate: Teach others how to interact appropriately with your dog and remove your dog from stressful situations instead of expecting them to endure others pushing their buttons.

Tiredness

Lack of quality sleep can affect our dogs just as it can affect us. Keep an eye on your dog’s sleep if you’re concerned, and ensure they have adequate quiet, restful time and adequate comfortable spots to sleep to support their rest.

Medication

Some veterinarians recommend certain medications as an aid alongside behavioral modification training for some dogs with fear or anxiety. It’s individual to each dog if medication is the right fit, and which is best for them. If you ever want to know if medication would benefit your dog, it’s best to consult with your veterinarian, as trainers can’t advise you on medications or prescribe them, only veterinarians can!

Introduce calming activities

When introducing activities to help your dog decompress, remember that your goal is to move them from their fight or flight or “reacting” brain, into their rest and digest or “thinking” brain, where they’re capable of relaxing and learning. This can guide you in choosing some good activities based on dogs in general, and also based on the reaction your individual dog has to each activity.

You can think of these activities as working the opposite way that stressors do for your dog: moving them farther away from their threshold instead of closer to it.

Below are some ideas.

Sniffing

Snufflemats

Food or treat scatter

Sniffari/Sniffy walk (in a place without their triggers - you may be able to rent one on Sniff Spot or somewhere similar!)

Scent work / nose work games at home

Licking

Frozen stuffed kongs

Lickimats

Chewing

Dental chews

Non-rawhide edible chews that you can scratch/dent with a fingernail (harder can crack/chip teeth for some dogs)

Chewable toys, plain or smeared with dog-safe-goops (wet food, yogurts, peanut butters, etc. without any artificial sweeteners or flavorings).

Dog-safe fruits & veggies frozen or stuffed (try in small doses first to make sure they don’t upset your dog’s tummy)

Safety first!

With all chews, keep in mind that you don’t want your dog to swallow large pieces of treats/toys whole or chew things that splinter, to avoid risk of choking or internal obstructions/damage.

It’s also important that they not crack or chip teeth on their chews, as some chews can be very hard.

Supervising your pet especially with any new chews is a good safety practice!

Check in with your vet on any chews you’re uncertain about.

Scavenging/Foraging

Puzzle toys & Slow feeders

“Trash box” DIY puzzle feeding

Low-stakes “for fun” training games & trick training

Rest

It’s okay to take days off from long walks or training. In fact, it’s encouraged! When we’re doing hard work studying for classes, or training at the gym, we have to take breaks to rest, recover, and process what we’ve learned, and our dogs can benefit from this too.

Consider doing some indoor exercise/enrichment instead for at least one day a week to let your dog have some restful time.

Don’t forget to take care of YOU too!

You can get overwhelmed too - and living with a reactive dog can be stressful. Sometimes, you may need to take a rest day from training because you are overwhelmed, and that’s okay! Let yourself take rest days when you need them and don’t forget to engage in some decompression activities to help your stress levels. Plan some occasional activities that are just for you, and some that let you have fun with your dog without the pressure of managing their reactions around their triggers.

Cade, with Argot Animal Training LLC